Sermon for 5Oct14 Matt21:33-46; Is5:1-8; Phil3:4b-14

Begging your pardon, but I’m going to start with algebra, trying to turn the diabolical instead to the Lord’s service.

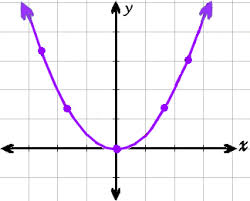

Actually I want to play with an algebraic word: parabola. A parabolic curve, you may remember, looks sort of like a U. Not incidentally, is related to the word “parable.” Both are from the Greek meaning “to go alongside.” For the math symbol, we can literally see two arms side-by-side. We could think of the spoken parables as analogies, as illustrative examples.

But moving toward my larger point—and here’s where we get a bit math-y—is that parabolas start out going one direction, then all of a sudden turn the other way. On a graph, the values would get smaller, smaller, smaller, then reverse and get bigger, bigger, bigger. If you were expecting a trajectory, this is a complete reversal.

And what I’m really meaning is that Jesus’ parables are often parabolic. They start out going one direction, then flip to the other meaning, catching you off guard. I’m not sure if that’s exactly the intention in using the word parable for them (but there’s a fair amount I’m not sure of this morning).

So think of the most famous parables, both in Luke’s Gospel. In the Good Samaritan, we listeners expect that the nice, holy people will stop to help the beaten up half-dead guy. But it’s the miserable, foreign, heretic Samaritan who is the hero. Or in the Prodigal Son, with that lousy son as the main character we think it’s going to be a morality lesson, of him repenting for squandering his father’s property. But before he even gets a chance to apologize, with a sudden change of direction the father has run out to welcome him, bringing him home.

Instead of thinking of parables as straightforward explanations, actually it repeatedly says in the Gospels that Jesus used them for subversion, or confusion, maybe to make people ponder. As one author says, “Far from being an illustration that shines understanding, it is guaranteed to pop every circuit breaker in their minds” (Capon, “Kingdom, Grace, Judgment: Paradox, Outrage, and Vindication in the Parables of Jesus,” p6). Which makes sense, since if you’re trying to talk about what God is up to in the world, there’s mystery and uncertainty, right?

The surprise flip-flop is in a lot of parables. Jesus talks about the kingdom of heaven as yeast, a ritually unclean substance for his people. He says that it’s like a mustard shrub, hardly the largest of trees, and actually a pesky weed for farmers. And the very birds that Jesus praises for dwelling in it would be the ones to gobble up the farmer’s crops. We’ll come back to that agricultural reality in a bit.

But first let’s presume for a moment that the regular reading of today’s parable is “right,” that it’s an allegory for the Bible’s story, each detail stand for something else. In this analysis, the tenants in the vineyard are God’s people, but they aren’t providing the good things God expects. So God sends servants, interpreted to be Old Testament prophets, but the laborers don’t listen to them. Instead they beat them up and kill them. (Indeed, there are stories of prophets like Jeremiah or Elijah having it pretty rough.) Finally, God sends the Son, whom we identify as Jesus, who is also killed. Thus far, the extended metaphor works okay.

Though we could be skeptical about calling God an absentee landlord, what comes next is not at all how we characterize our God. It says that the owner “will put those wretches to a miserable death.” Really? Do we expect God is out to murder us if we haven’t produced enough fruits, haven’t paid up what we owe? If God stands for the owner in this parable, it would really alter our view of God. Which also brings up that the owner sends the son thinking that surely the misbehavers will listen to him. But would we claim God expected that? Shouldn’t God have known the son might end up getting killed?

So what if that’s not how we’re supposed to hear this story? Let’s try another line of interpretation. To get a whole different set of images in your mind, picture a place far away from centers of power, where it’s easy for a small group of extremists to seize control. They militantly take over the resources of villages. Then they behead an American journalist. And you know how the parable ends: the Americans will come and unleash even more violence on them and “put those wretches to a miserable death.” The facts and details really are the same with hearing the Islamic State in the story as when Jesus tells it, but it’s a dangerous adaptation.

Yet again, what if the parable is literally about tenant workers in a vineyard? When the master tries to collect, either the workers refuse, or else they simply can’t pay. Maybe it was a bad harvest. Maybe the price of rent was too high, and the price of grapes too low. Extreme debt was the biggest social problem in Jesus’ time (which is why the best translation of the Lord’s Prayer wouldn’t be about trespasses or sins but about debts and debtors, prayed by people who literally had no bread stored up for today).

But that situation of debt is just as epidemic in our time. It’s true for farmers with low corn prices this year. It’s true for Scotch Hill Farm, that can afford to rent less land each year because the cost keeps going up. It’s true of us as individuals, plagued by credit card debts, blindly imagining we can keep consuming, which is the central reason we’re offering Financial Peace University again. It’s what caused the Great Recession, with Wall Street greed of the big banksters and too many of us sucked into bubbles, getting in over our heads. It’s even true on international scales when lesser developed countries go bankrupt over interest on loan payments.

Backed into that corner, what’s the answer? Personal responsibility is fine and good, but when it’s predatory and institutionalized, then what? Some reforms may come from the ballot box, but such comprehensive solutions weren’t possible in Jesus’ time.

So the story goes on that the workers revolted. With escalating violence, they killed those who were sent, trying to stake out a little claim and keep the inevitable at bay. But the inevitable has a way of catching up with you, and so the powerful master—quite obviously, of course—isn’t going to put up with it, but will come and kill them. It was the story then. It was true of feudal lords or sharecroppers. It is bleeding to death by a thousand cuts still with debts today. At the Poverty Summit this week, it was in stories of lives that completely fall apart because of being short just $50.

So where’s the point of the parable? Does it side with the master, who may even represent God? Is it in favor of the poor, oppressed workers, whose fate may be the same as the friends and family of Jesus? For context, remember that African American slaves and plantation masters were both Christian, but with vastly different directions for their faith. Or does trying to decide the meaning and find an answer just highlight our selfish prejudices or needs?

Let’s step back to notice something else: Either way there are sides, and both sides turn to violence in trying to get their way. Any of these decisions to act come as a response for feeling at a loss, short-changed and abused. It sets up a competition, a conflict that is never resolved. Even when you’re ahead, you feel like you’re behind. There’s just no end to it. That is called, plain and simple sisters and brothers, the rat race. On this weekend of St. Francis, we may say that rats have a place in God’s creation, but God did not create you to be a rat in a race.

No, as Philippians sets before us, the race and the goal is not any of those competitions. It’s not in how you can get ahead. It’s not in the violence of trying to oppress others. God did not create you to count your credits against others’ demerits, to compare your surplus over another’s lack, to measure your gains by what others lose. No, if you think those are gains, you’ve already lost, because the goal, the destination, and even the course of your race is none other than Christ.

And that makes everything else rubbish, garbage, crap, our favorite Greek word: skoobala. When everything you wanted to invest your best in turns out to be fit for the sewer, that stunning reversal flips all of life on its head, the parabolic curve that turns all of your intentions around. Christ even changes the meaning of death.

Life, then, is in continual striving to be Christ-like, making us ourselves the vineyard. The fruits we produce aren’t for selfishly storing up. We exist in order to nourish others, as Christ gave himself that you may live, so may you share freely and abundantly what you’ve been given with all your life, joined with love into the enormous sister- and brotherhood of creation.

But here’s the ultimate parabolic twist and turn: even if you don’t do it, even if you can’t, even if you’re stuck in the rat race, by God Christ still loves you. Already he is with you, not just trying to nudge you to do more, to be a bit better, not waiting for you to achieve or produce, but already lavishing you with every blessing.

Hymn: We Raise Our Hands to You, O Lord (ELW #690)